Draw Your Weapon!

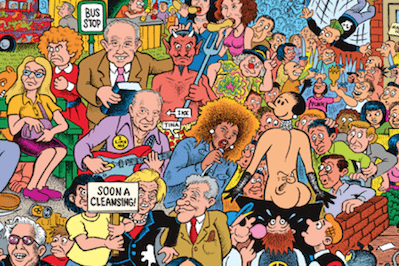

“The Realist Cartoons”

When Aristotle said “The gods too are fond of a joke,” he was commenting on the inauspicious similarity between gods and mortals. “Most people enjoy amusement and jesting more than they should … [A] jest is a kind of mockery, and lawgivers forbid some kinds of mockery—perhaps they ought to have forbidden some kinds of jesting,” he added.

While the 20th century Greek classicist and literary critic C. A. Trypanis wrote that “comedy is the last of the great species of poetry Greece gave to the world,” many famous Greek philosophers considered humor morally corrosive and antithetical to sound reasoning. Plato believed that comedy, because of the anarchistic mood it promoted and inspired, needed to be controlled by the state. He went so far as to characterize humor as a malicious vice debilitating to rational self-control. “We shall enjoin that such representations be left to slaves or hired aliens,” he wrote, “and that they receive no serious consideration whatsoever.”

Nearly 2,500 years later and with several hundred decades of evidence to support an opposing point of view, it is now undeniable that Plato and Aristotle were wrong. There is no greater exemplar of sound reasoning—and no greater filter of politics, religion and the media—than humor.

It is arguable, given the cartoons and cartoonists so lavishly celebrated in Fantagraphics’ new release, “The Realist Cartoons,” that without humor we would not have such a precise tool with which to ridicule—nor the incentive to deviate from—the myopic mainstream narrative that would have us believe that the government, or at least the party with which we choose to identify, is consistently maintained by wise and benign stewards of justice. Humor also shows us that morality is measurable by how well we surrender our natural curiosity about how the world works to unimaginative bureaucrats tasked with telling us precisely how it should work.

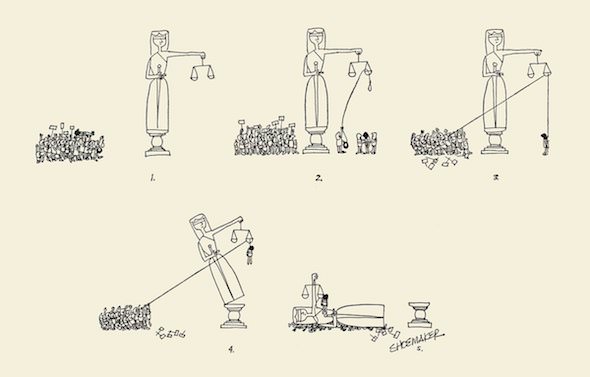

Satire, particularly in the form of cartooning, has the power to reshape our comprehension of absolutely everything in pursuit of a surprising punchline offered in contempt of conventional deduction. Humor upgrades the dexterity of our thinking and convinces us of the subjectivity of truth and of our need to interact with one another using means beyond the political, religious and cultural contrivances on offer from the more traditional modes of perception, reflection and motivation.

In sharper terms: It turns out that, yes, bullshit is, in fact, fertilizer.

Paul Krassner began publishing his satirical magazine, The Realist, in 1958 and stopped in 2001, finally upstaged by real world events whose tragedy and absurdity trumped any and all satirical contrivances. After all, it was during that year on September 11 when the United States was attacked by 19 men with box cutters who ended up killing nearly 3,000 people. The date of the attack also happened to be the 126th anniversary of the initial publication of the very first newspaper comic strip in the United States, Professor Tigwissel’s Burglar Alarm. It was published by the New York Daily Graphic newspaper, whose offices had been located some 5,000 feet away from the site of the World Trade Center.

Appropriately, the strip depicted a self-aggrandized egomaniac who attempts to protect himself from the threat of a home invasion by stockpiling excessive firearms and weaponry and installing a foolproof security system designed to prevent a surprise attack. In the comic strip, the firepower and security system don’t work and Professor Tigwissel is attacked, but he arrogantly claims success afterward. He promises to patent his device to perpetuate the notion that we are best protected by the machinery of our paranoia and a weaponized mistrust of the world rather than a less hysterical adherence to truth, justice, humanitarianism and mutual cooperation. Such was the premonitory power of the cartoonist in 1875, and such was the sickening plunge of real life into the realm of gruesome fantasy many years later that rendered the satire of The Realist no longer allegorical, but literal—literalism being to allegory what a real fire is to a crowded theater.

The demise of The Realist, which is now being called the “Charlie Hebdo of American satire,” and which writer Terry Southern referred to in the 1960s as “the first American publication to really tell the truth,” also was due to the ever-increasing corporatization of American democracy and the blatant commodification of artistic free expression by unimaginative businessmen and their marketing departments.

Specifically, where there once existed a well-informed anti-authoritarian audience for satire, Americans became passive consumers of inconsequential burlesque masquerading as satire. People assumed corporate-sponsored jokes that merely used political personalities and circumstances as fodder the same way that slapstick used seltzer bottles and baggy pants were somehow the same thing as sharp and unforgiving criticism by uncompromising freelancers for the deeper purpose of revealing political and social injustices and commenting on them in a way that engenders more psychic pain than physiological pleasure. The idea became that humorists in search of laughter alone over frank and honest outrage are not satirists for one simple reason: Mirth cripples rage, and rage is necessary for the beating back of political, cultural and religious bullshit in service of change.

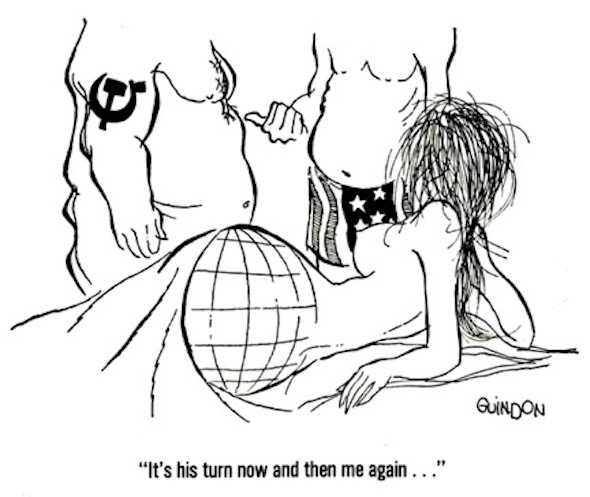

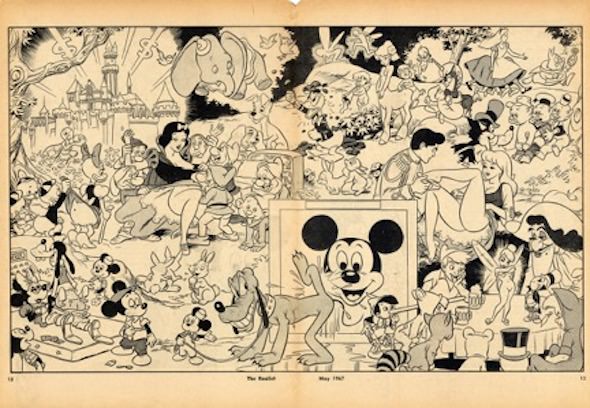

In Krassner’s freewheeling and illuminating foreword in Fantagraphics’ “The Realist Cartoons,” we learn of his hilarious beginnings with MAD magazine; his being deemed the father of the underground press (he demanded a paternity test); and his support of, fellowship with and advocacy for the greatest satirists, comedians, social critics and freethinkers of the mid-20th century. We also learn why the infamous Disneyland Memorial Orgy cartoon by Wally Wood and the Fuck Communism poster created by Krassner and John Francis Putnam are as important to the protection and promotion of our civil liberties as sit-down strikes, bra-burnings, boycotts and street demonstrations. (The proceeds from the poster helped a young Robert Scheer travel to Southeast Asia in 1964 to report on a little known conflict brewing in a faraway land called Vietnam.) All this heady stuff is made more grounding and eloquent by the size of Krassner’s heart and his desire to rescue us from drowning, not by throwing us a life preserver but by teaching us how to swim.

I teach a course at the University of Pennsylvania about the history of art as commentary. I rely heavily on the cartoons of The Realist, specifically because of the magazine’s long history battling censorship and charges of indecency. Each semester I assign a paper designed to show how the concept of obscenity is a socialized construct rather than an innate reaction to an external phenomenon. For the assignment, I ask the students to search for a piece of art that is personally offensive to them and then to defend its right to exist. After the papers are turned in, I ask the students to tell me about the experience of searching for offensive art, and each semester they tell me that the task was nearly impossible when they searched alone because nothing was truly offensive to them. Only when they looked for images with other people around did they feel shock or shame. The exercise is analogous to reading, writing or saying a dirty word while alone versus engaging with so-called obscene language in a public space. The former inspires no reaction whatsoever and the latter causes real and genuine discomfort, proving that obscenity, like patriotism, typically requires a herd mentality in order to be conjured.

I explain to my students that it is in that private space, in that state of aloneness, that most artists and satirists conceive their work, which is why some artwork can appear vulgar in its honesty or obscene beyond its intention when viewed in public. Put bluntly, you are more likely to pick your nose or scratch your ass if you are alone than if you are in public, and it is with that clarity of purpose and egoless satiation of a dilemma that artists enunciate their undiluted utility most succinctly. And that is why art as a language has great potential to enlighten, because it operates with fewer restrictions and fearlessly uses the blade of honesty more than many methods that may be more publically sanctioned.

A number of cartoonists who regularly produced work for The Realist also cartooned for The New Yorker, The Saturday Evening Post and other mainstream publications. But, according to cartoonist Mort Gerberg, Krassner’s magazine was the only periodical in America for which they could draw the cartoons they really wanted to produce. It was the only publication that permitted them the rare grace of maintaining their artistic integrity without compromise.

More than simply a collection of cartoons, “The Realist Cartoons” is an instruction manual for those wishing to learn how to speak bravely and frankly about race, sex, war, peace, abortion, doomsday, environmentalism, free speech, civil rights, homosexuality, human rights, human wrongs, love, hate and obscenity—to learn, that is, by exquisite example.

While I think this book is essential for anybody whose appreciation and knowledge of the form is already established, I also offer it as contrary proof to those who dismiss editorial and political cartooning as a pointless feat of oversimplification. There are certainly examples of cartoonists who dumb down political discourse, just as there are writers who commit the same violation, as well as other kinds of artists and public intellectuals who dumb down the entirety of our cultural acumen with the ideas they promulgate. Rather than look to the whole profession, it would be more instructive to look to the individual artist or thinker—and the circumstances that produced the commentary being offered—to assess whether participation in a dialogue is additive or subtractive.

It should not be overlooked that a great deal — some might argueall — political discourse is a very deliberate dumbing down of humanitarian discourse. (Recognizing the need to reverse our negative impact on the environment, for example, is made perverse by the political notion that nothing can be done to save the ecosystem until a solution is devised that doesn’t impact the business sector.) And while I might agree that the majority of cartoonists published over the past 300 years could legitimately be accused of simplifying political conversation, I argue that, by and large, they are not doing it for the purpose of dumbing down discourse, but rather for the purpose of introducing clarity, common sense and sympathy into the national political dialogue.

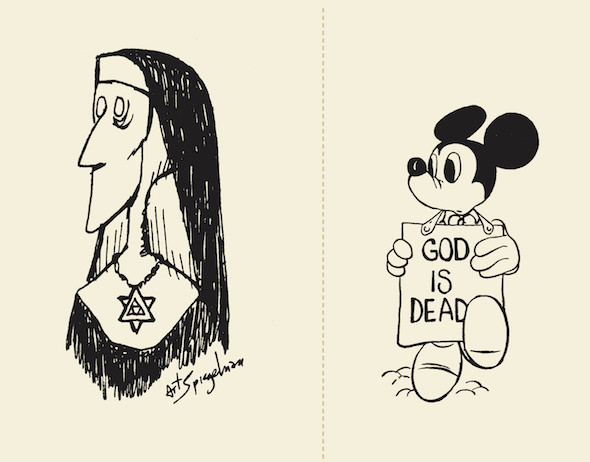

Cartoonists, when they succeed, make politics accessible and understandable and, quite frankly, usable to a large portion of the public who, because of race, education level, income inequality or any number of reasons, would have no easy way to decode and decipher how and why the world functions and dysfunctions as it does. When one considers the incredible roster of cartoonists who appeared in The Realist — cartoonists such as R. Crumb, Art Spiegelman, Richard Guindon, S. Clay Wilson, Skip Williamson, Wally Wood, Bhob Stewart, Mort Gerberg, Sam Gross, Falcon and Nicole Hollander — it is relevant to add that a cartoonist, in addition to making politics accessible and understandable, is also useful in making radicalized ideas of dissent and civic and social engagement accessible, understandable and, in a word, hip.

For obvious reasons, the timing for such an inspiring collection of razor-sharp dissent and gut-busting dick (and dickless) jokes couldn’t be more perfect.

Mr. Fish

Cartoonist

Mr. Fish, also known as Dwayne Booth, is a cartoonist who primarily creates for Truthdig.com and Harpers.com. Mr. Fish's work has also appeared nationally in The Los Angeles Times, The Village Voice, Vanity…